Research

Living systems are diverse from gene sequences to organismal morphology to communities and ecosystems to the largest global patterns. Our goal as biologists is to document this diversity and understand the complex interactions and dynamics that generate and sustain biological variation. In our lab we bring together scientists with different skills, from taxonomists to computer scientists, to work together and investigate biodiversity from different perspectives. We have a particular fondness for ants, given their ecological dominance and spectacular evolutionary adaptations, but have worked on a variety of organisms over the years.

Evolutionary Phenomics and Innovation

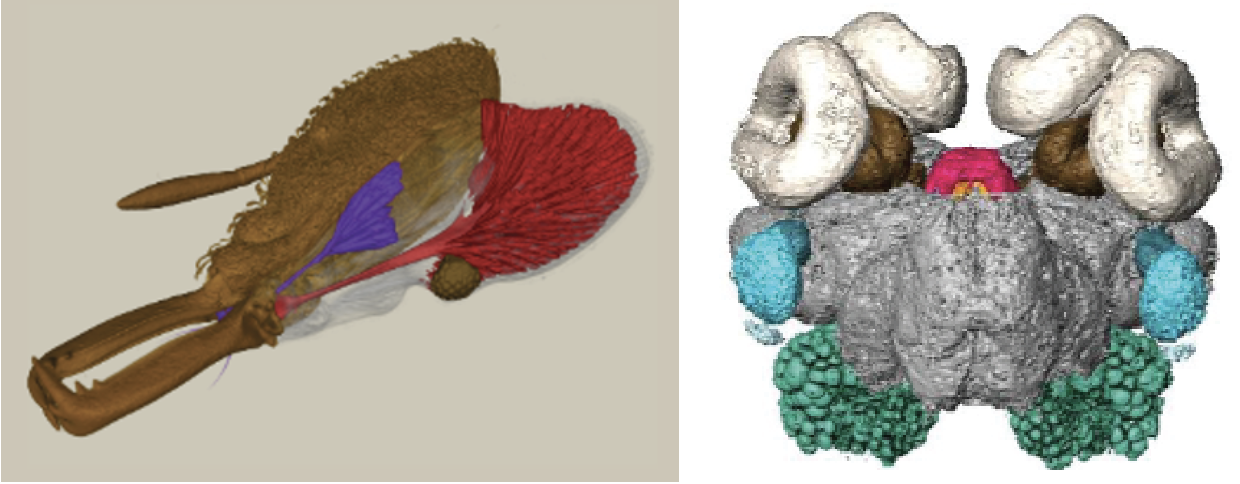

Images: Booher et al., 2021 PLoS Bio., Gautam et al. 2025, Proc. B.

How does evolution generate diversity and complexity?

We aim to understand how functional systems of the ant phenotype evolve, including the origin of novel functions, such as the trap-jaw mechanism, and diversification of the key systems: brain, locomotion, mandibles, eyes, digestive, and others. More broadly, we are studying how ant shape evolves during diversification and adaptive radiation. Which parts of the ant body evolve quickly and slowly, and what does this say about the constraints and forces shaping evolution? In addition to projects on ants, we have worked with collaborators to study the evolution of other interesting traits, such as bird beaks and fish brains. Much of our work in this area has centered around our long-term efforts to develop micro-CT for phenomic characterization of small insects, and you can check out our gallery of 3D models on Sketchfab.

Global Biodiversity

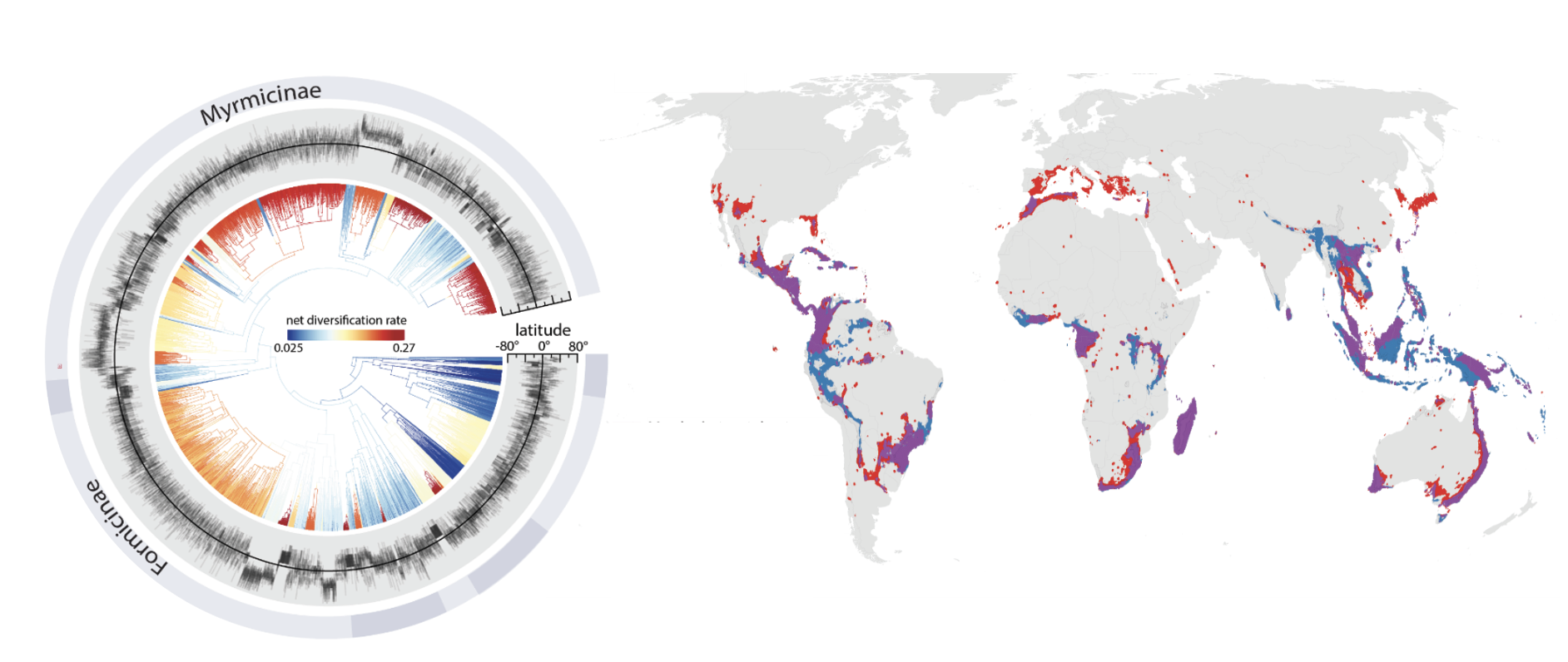

Images: Economo et al. 2018, Nat. Comms., Kass et al. 2022, Sci. Advances

How is Earth’s biodiversity distributed around the world, and what explains these patterns?

We’re interested in large-scale patterns of diversity and the evolutionary and ecological processes that shape them. This involves synthesizing and integrating two basic data types: the spatial distribution of each species on earth and the phylogenetic relationship between them. Biodiversity patterns in invertebrates, such as insects, are especially poorly documented despite representing the large majority of species. To address this knowledge gap, the Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics (GABI) project has compiled over 250 years of ant research into a single database providing distribution information for all ant species. We built a website, antmaps.org, where you can interact with these data. We have also worked on reconstructing large-scale phylogenies and studying global diversification, for example the hyperdiverse ant genera Pheidole and Strumigenys.

Ecology of the Anthropocene

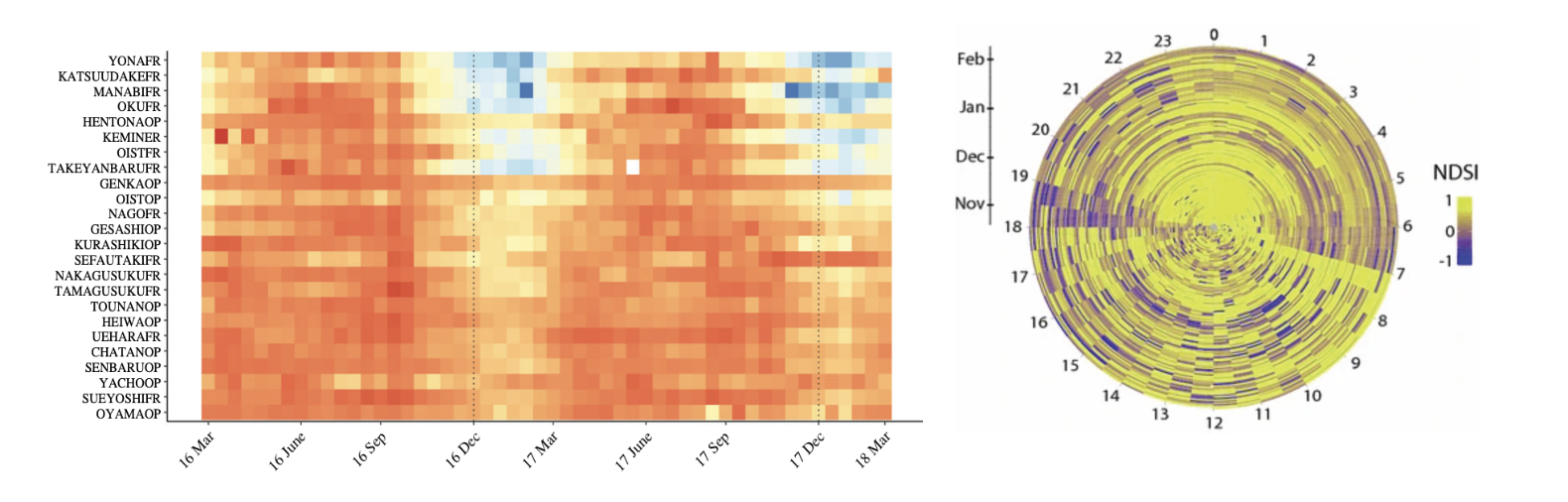

Images: Kass et al. 2023, Proc. B., Ross et al. 2018, Ecol. Res.

How are insects and other understudied, hyperdiverse groups faring in a changing world?

There is ample evidence that biodiversity is in crisis due to the multifacted stressors of the Anthropocene. However, for many species, and in many places in the world, we have little or no data to track what is happening to them and the ecosystems they are a part. This is especially true for hyperdiverse invertebrate groups such as insects in tropical and subtropical regions. We have a long-term interests in the ecology of islands, as they are good model systems for what is happening around the world. Another focus is the worldwide spread and impact of introduced ants. More generally we are interested in new approaches to quantifying biodiversity and monitoring change, experimenting with ecoacoustics, metabarcoding, imaging, and other technology. Much of this work grew out of the Okinawa Environmental Observation Network (OKEON), an initiative we led to perform community-collaborative research in Okinawa.

Biodiversity and Emerging Technologies

Images: Economo Lab

How can new technologies change biodiversity science and how the public interacts with biodiversity?

Biodiversity science is an information science, thus the “information revolution” will continue to have huge impacts and create new opportunities for both our science and how society interacts with biodiversity. Advances in large-scale digitization, imaging, sequencing, computation, allow us to capture and analyze information about biodiversity on scales that were once unimaginable. Moreover, we have new ways to interact with biodiversity information, such as augmented reality and virtual reality, which provide new opportunities to share the diversity of life with the public. Most of our work centers on how technology interacts with biodiversity collections, and in the coming years we plan to work on new technologies for collections-based science.